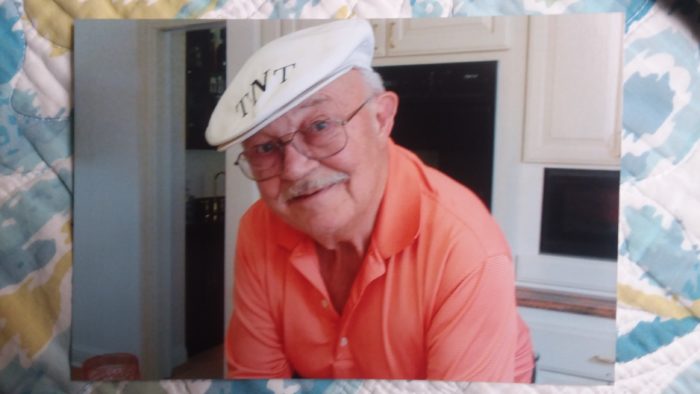

Orest Danysh

September 9, 1933 - October 22, 2021

Obituary

(Note: In lieu of flowers, please consider a donation to the Ukrainian-American church community Orest and Nadia dedicated so much time and love to – Our Lady of Zarvanycia Church – 5321 17th Ave S, Seattle WA 98108.)

Dziadzio’s (Grandfather’s) Obituary

For me, I picture Tatusio (father), in death, as a beautiful large crystal breaking into a thousand pieces. His light is in all of us now, and our task is to carry it on, with love and pleasure.

An obituary, literally meaning a record of how a person went forth encountering death, is actually meant to inform and remind us of the journey someone lived in their lives, and in the case of Tatusio’s long and happy life, it’s the story of an example set, that his grandchildren, friends and family can admire and emulate. This “story” is dedicated to his two grandchildren, my niece and nephew, Carlos and Berkeley – may they discover here new nuggets of delightful information to light their path. 😊

Tatusio was born in an auspiciously terrible year – 1933. In Ukraine, it was the last year of the Holodomor – the two-year period 1931-1933 when literally millions of Ukrainians starved to death in a genocide engineered by Stalin’s forced “collectivization,” which stole every last kernel of grain from farmers and families in greater Ukraine, which was just over the Zbruch river bordering not far from Tatusio’s home in Ternopil. It was also a terrible year for Jews and the western world – the year Adolf Hitler took power as Chancellor of Germany.

Far enough from these tragedies, Tatusio at birth traced a few generations to the wonderful little village of Ilavche where beloved family members still live, and otherwise your Dziadzio had a heck of a time in summers playing in the fields and “helping out” on the farm of his maternal grandfather, Nicholas (Mykola) Procyshyn, in the village of Nastasiv.

Before his brother, Bohdan, was born – 10 years after him – Tatusio had a sister he adored, Khrystia, who died tragically from a curable disease at age six, on her mother Maria’s birthday. The story goes that she would have recovered had the family cared for her at home, but being an educated, more well-off family, they had to show faith in the hospital system, so she was taken there, and died.

Tatusio had a happy childhood when he was little. His father, Ilya, one of the youngest of 10 children who sold off his portion of the family land to go to university in Vienna, later was an officer in the Austro-Hungarian army in World War I, became a biology professor as they were called then at the local gymnasium or high school in Ternopil, and still later became a director in the cooperative banking system, built a large, modern, sturdy home on Vahylevych Street in Ternopil, which you can visit today – Tatusio was fortunate. He had a best friend, Roman, who lived on that street, and who no one was ever able to trace after the war.

You must know of the story of how Tatusio fled with his family in March of 1944, when the Germans and Russians were literally fighting on the streets of his town and everyone lived blacking out their windows day and night so as not to attract a grenade. Even Anne Frank mentions this fighting in Ternopil in her diary.

But the story of flight is an interesting one. Ukrainians knew that no matter how bad the Germans were, the Russians, their old enemies, would be far worse. Our family knew they would undoubtedly be deported to Siberia. Tatusio’s father, given his status and education, was just as likely to be summarily shot, or, as an already middle-aged man, die along the way. So Babcia, ever the enterprising wife 12 years her husband’s junior, bribed a German soldier with a pig to let the family escape in the back of his truck in the convoy leaving Ternopil in defeat.

Well, the family was discovered when they reached the border between Ukraine and Czechoslovakia, thrown out into the woods in the snow, and felt lucky that they were not shot on the spot.

The rest of the story was a “success” because given your great-grandfather Ilya’s perfect command of German and stashed away lifesavings, the family was able to buy or bribe their way onto trains and eventually reach Switzerland, even though it was a long journey in which you hoped to get down the tracks some distance, then your car would get de-coupled and you would sit waiting for an opportunity to keep going, and sometimes you were coupled to a train heading back in the wrong direction, and you paid dearly to return again.

At first sheltering on farms and then living in displaced person’s camps for six years in Switzerland and Germany, Tatusio stayed very busy doing his part in the family, and tells stories among others of going out to catch fish in streams with his bare hands. Mamusia told me that at times his family was starving and had nothing to eat but grass – but he would not tell us that story. He instead tells stories of how every evening the youth and adults sat in the entryways of their barracks at the camps and sang Ukrainian songs all evening, and how nice it was.

He tells how he went to a high school in the French zone – post-war Germany was partitioned into four parts – and that his “professors” taught in whatever language they spoke – he had biology in Russian, math in German, philosophy in Serbian, and of course English and French.

He also tells how his class was made up mostly of girls, all of them older and taller than him, and they all wanted to learn how to dance properly, so he got a lot of good practice. He also tells how a teacher once called him to the front of the class, to show the example of the round head of the inferior races of eastern Europe.

When the war ended in 1945 and soldiers were coming around to every door, strongly encouraging Ukrainians to get on trains back to their homeland (to enjoy the “freedom” of Soviet communism, in the eyes of some poor, naïve youth who had been “guestworkers” in Germany too long, missing the horrors of war in Ukraine), his ever-resourceful mother, Maria, faked terrible illness, and alas, they just had to remain. 😊

Fast-forwarding to New York, your Dziadzio at age 17, passed through Ellis Island in 1951 with his dad, mom and little brother, and what work didn’t he do? He started out at a bakery clocking in at 2 a.m., very convenient according to him, sometimes going straight to work after a Ukrainian zabava (dance). Next, he worked in a chocolate factory arranging chocolates in their boxes, enjoying the company of the Italian girls around him laughing and gossiping. He also was lucky enough to get recommended to work for an optician and learned how to use a machine which ground eye glasses, a job that honed his love for precision and perhaps sparked his interest for future technical studies.

His father, a former bank director now working as a janitor in their tenement building, passed away a year later at age 68 in the basement of their building, where he was found slumped in a chair by your uncle Bohdan, a boy of eight then, and is buried in New York. Tatusio’s mom, now in need, wrote her brother in Detroit and the family moved there to live in the double-decker on Mitchell Street.

War came again. Since it was better to enlist rather than waiting to be drafted for the Korean War, Tatusio joined the army at 18 and after training at Fort Bragg, and some brief stay at the base here near Tacoma, now Joint Base Lewis-McChord, Tatusio was shipped to Japan where his language skills were utilized in translating and summarizing Soviet economic news. He was so well-liked by his commanding officer that he found a way to take Tatusio to work with him in his deployment to Korea, where for some period Tatusio had the dangerous job of working as an artillery spotter near the “contact line”, but later worked in the officers’ club, and had some good stories to tell about at least one Colonel.

Back in Detroit after the war, Tush not only had a veterans’ privilege to enroll in college and become a citizen within two years – much faster than everyone else – but he saved up his money and bought a gorgeous black and white “MoTown” Chevrolet De Soto. A friend predicted that with a car like that, he’d soon be married. Wise prediction.

One of the biggest keys to Tatusio’s character, which virtually all of you reading this know, was the incredible emotional union he formed and remain true to – with his beloved wife Nadia, our mother.

But until a certain beautiful autumn day in 1956, it wasn’t that way.

Tatusio and Mamusia crossed paths as children in a displaced persons camp where Tatusio’s father was actually teaching school subjects to children, including our mother, your Babcia. She was four years younger, and later, as a skinny 12-year-old, she practiced ballet in a small hall there at the camp, and said she’d see that handsome boy Orest playing soccer with his friends, and she would leave the window open and practice near it, hoping he would perhaps hear the music and catch a glimpse of her.

Years later, that boy was a strong young man in his early 20s, playing a soccer match in Toronto, when he caught a glimpse of the beautiful young Nadia, who now lived there, and it was his turn to pay attention.

Nevertheless, the story goes that when she was just about to turn 18 and had to decide whether to eventually become an American or Canadian citizen, (having first lived in Rochester, New York), she moved to Detroit, and Tatusio’s mother ordered him immediately to go and buy a dozen roses and welcome Nadia Makuch who had just arrived. Well, a dutiful son, he bought the flowers, found Nadia wasn’t home, and decided to go back to the soccer pitch, distributed the roses among his friends, and got on with a game.

But not long after, one lovely fall day with autumn leaves turning, Tatusio, again the dutiful son, was parked in his car, waiting outside the Ukrainian church for his mother to take her home after the Ukrainian Women’s League meeting. Well, a certain Nadia was also at the meeting, found it rather interminable and exited early, your Dziadzio saw her come out, called to her, politely chatted, invited her for a drive in the gorgeous hills of some lovely neighborhood, and the rest is history.

How his mom got home, or what she said when she found her son missing, we’ll never know. 😊

These were the old stories, Berkeley and Carlos, that perhaps you didn’t know. But the rest, you must know pretty well from your father.

So I’d like to mention a few of the facts of Tush’s life that stand out for me, that I am proud of, that made him the man we knew.

Some men and women focus their attention on their children, but not Tatusio. That bond he built with Mamusia, despite all the ups and downs of their married life, were at the center of his existence, and the role he played was that of a family man. We were an inseparable unit of four, and either he and Mamusia made decisions together – because they had the same exact values – or he deferred to her wishes.

I note to myself now, since I so very deeply admire my father, that looking back, he seemed to live a very ordinary daily life, not necessarily setting his sights on sacrifice or service. Well, he didn’t need to. His beloved wife was someone who never got out of her soul the deprivation and tragedy she experienced during and before the war as an orphan – and so all her adult life, she had a burning need to sacrifice, to help, to take under her wing – and Tatusio was her faithful accomplice.

It goes without saying that their lives revolved around the Ukrainian community, and whatever the community needed, they were more than willing to volunteer. Did Fr. Joe need to be picked up at the airport? Did the Kihichacks need to be picked up from the ferry on the way to church? Did Mamusia need to bake one more pliatsok for a community gathering, or welcome a new family to town, or buy presents for someone’s grandchild? They both, as a unit, did these things.

How many millions of times did we hear in our house fall from Mamusia’s lips, the word, vypadaye. Which means, literally, this thing is the appropriate thing to do. And what we all know, is that that word summed up the heart and soul of Mamusia’s and Tatusio’s values: generosity.

What it meant was: Mush feels the need to do this thing for someone, and so it’s time for Tush to swing into action — which he never hesitated to do, because of love for her, and unquestioning commitment to the community.

In their effort to merely do their part, they took their turns as leaders. Mush led the Sestrytstvo for a while, the Sisterhood at church, and Tatusio, you may know, was one of the first presidents of the Ukrainian Club of Washington, a responsibility he carried out for 10 years. It wasn’t because he was seeking authority or admiration – far from it. He simply thought it was time for a changing of the guard, and stepping up yourself was one way to do that.

One of our favorite parts of his presidency were his speeches down in the basement of St. James Cathedral’s dining hall, especially at Christmas time when our Ukrainian Catholic parishioners all gathered for a potluck meal. He was always warm, funny, managing to be deeply sincere, positive. All was said with good will. To put it simply, we were so proud of him because he was loved by all, young and old alike. He worked hard on those speeches, but he expressed them seemingly off the cuff, with a smile and a joke always lurking in his words.

You probably know that Tatusio was voted Employee of the Year at Boeing in 1981, where he worked all his life. I’m not sure if you know of the famous story that I just love about “benign neglect.” He tells it that when he came to make his speech before a large crowd at a luncheon in his honor, with all sorts of Boeing vice-presidents in the back listening, he told the audience of his managerial philosophy, which he called, “benign neglect.” The vice-presidents pricked up their ears in alarm. But Tatusio went on to explain, “That’s right. When someone comes to me with a problem and they want me to solve it, I tell them in a very friendly way, ‘Go back to your desk. Work on it. Think again. You’ll figure it out.’ And they rarely came back; they solved their problems themselves and gained confidence.”

Another thing I’d like you to remember, Carlos and Berkeley, is that your grandfather had a beautifully balanced character. He not only served and enjoyed the Ukrainian community, carried out with devotion every task his wife wanted him to do, and raised his children with love, affection and that foursome-family-unity I spoke of (which took the four of us on many a Sunday drive to experience American culture and nature), but he also just enjoyed life for himself.

Your Dziadzio was not only an inveterate golfer, but was also a devoted fisherman for decades, as mentioned a semi-professional soccer player in his youth, (“All the rest of the team play for 90 minutes,” the soccer announcer spoke, “and Danysh played for 100.”), a competitive volleyball player, and an enthusiastic skier. He also embroidered all those beautiful pillows in our living room, and carved the lovely large Forget-me-not flower hanging on the wall, and he read all the science fiction books he could find at our local library.

But on a very different note, let me ask you – what does the word “sacrifice” mean to you? I’ll tell you one story. When your great-grandmother Maria was 75 years old, Tatusio took his mother in to live with him and his family – for 20 long years – and cared for her in her dying months. The friction that this caused in his marriage, the guilt that he felt creating more stress for his wife, the patience he always practiced to smooth things out, yet the unquestioned responsibility to keep care of his mother to the end – this was sacrifice.

But there were good times. When your Babcia and Dziadzo were able to get their kids out of their hair, (when your dad and I went off to college), Tatusio would drive to pick up Mamusia downtown on many a Friday night and they would go out for dinner and movies. They went on a trip to Austria, they remodeled the house, and they worked with such love and joy in their garden, planting a small orchard and making jams of every kind, transplanting roses, replanting strawberry roots, making a riot of colors to grow in every part of the yard.

In these last several years when I’ve worked alone in this beautiful garden they created, Mamusia, gone from us, Tatusio unable to hold anything but a walker, I imagine that this was one of the unadulterated joys of their lives, this garden.

******

We all honor Orest Danysh, remembering the man he was. I want to leave you with last words on some of his most marvelous traits.

From my youth, I recognized that Tatusio was such a fair person, that he should have been a judge. Not necessarily in our courts, but in the sense of Solomon and his wisdom. He was equally friendly to everyone, he never approached a person with pre-formed bias, and neither did he shirk from politely telling anyone when they had overstepped the bounds of kindness and decency, or were hurting someone else. He did not judge people for the color of their skin, nor hold anything against the rich or the poor. He saw above all the humanity in everyone.

I simply cannot put my finger on one of his most beautiful traits – please help me. It doesn’t fit to say he was humble or modest or simple, nor that he was selfless or self-effacing – that’s all too strong. He was wonderfully free of egoism, vanity, and self-centeredness. He respected himself, he respected others. He was blessed with the maturity of a human being who values all people. He was a man of Community, he saw himself as one among many.

And this leads us to the trait that we all probably loved about him the very most. 😊 He was a people person who loved to be with others. 😊 Let me tell you, the good humor, the jokes, the smiles, the kindness, the warmth that all of you his friends and colleagues, and even strangers experienced – it was especially for you – it wasn’t for his family, whom he loved but who did not elicit this special level of joy from him. When he saw you, it all came out of him naturally – a sense of pleasure in being with others, exchanging a moment with them, getting to know them, or simply getting to enjoy their company yet again.

I can tell you, in his last few days, when he was no longer able to walk, talk, eat, or open his eyes, when his nurse, Tyler, was leaving him for one of the last times, Tatusio tried to nod good-bye in his direction.

Orest Danysh was a great man. Not because he achieved fame or high rank, but because he kept an unspoken pact with honesty, integrity, graciousness, loyalty, and love of others.

Carlos and Berkeley, we all have a tall order to fill.

But your Dziadzio would never have asked you to follow in his footsteps. He never presumed to tell anyone what to do. He didn’t even give advice – (thank goodness, says Auntie Irusia!) The most he might have said might have been, “Do your best. Enjoy life!”

What he would have left unspoken, given the person of honor he was, was his example to us: “And stick to your values.”

Висловлюємо щирі співчуття родині. Це – велика втрата… Коли в далекому 1993 р. ми (“новоприбулі” в Сіетл з України) познайомилися з подружжям Данишів, то були зворушені їх доброзичливим ставленням та підтримкою. Їх інтелігентність, любов до свого українського коріння, активна участь в житті української громади та церкви викликали шану і були гарним прикладом. П. Орест вирізнявся чудовим почуттям гумору, чоловічою харизмою та щирістю. Завжди тепло згадуватимемо його. Вічна йому пам’ять.